Implementation Notes

This section is a collection of implementation notes for the stack reconciler.

It is very technical and assumes a strong understanding of React public API as well as how it’s divided into core, renderers, and the reconciler. If you’re not very familiar with the React codebase, read the codebase overview first.

It also assumes an understanding of the differences between React components, their instances, and elements.

The stack reconciler was used in React 15 and earlier. It is located at src/renderers/shared/stack/reconciler.

Video: Building React from Scratch

Paul O’Shannessy gave a talk about building React from scratch that largely inspired this document.

Both this document and his talk are simplifications of the real codebase so you might get a better understanding by getting familiar with both of them.

Overview

The reconciler itself doesn’t have a public API. Renderers like React DOM and React Native use it to efficiently update the user interface according to the React components written by the user.

Mounting as a Recursive Process

Let’s consider the first time you mount a component:

const root = ReactDOM.createRoot(rootEl);

root.render(<App />);root.render will pass <App /> along to the reconciler. Remember that <App /> is a React element, that is, a description of what to render. You can think about it as a plain object:

console.log(<App />);

// { type: App, props: {} }The reconciler will check if App is a class or a function.

If App is a function, the reconciler will call App(props) to get the rendered element.

If App is a class, the reconciler will instantiate an App with new App(props), call the componentWillMount() lifecycle method, and then will call the render() method to get the rendered element.

Either way, the reconciler will learn the element App “rendered to”.

This process is recursive. App may render to a <Greeting />, Greeting may render to a <Button />, and so on. The reconciler will “drill down” through user-defined components recursively as it learns what each component renders to.

You can imagine this process as a pseudocode:

function isClass(type) {

// React.Component subclasses have this flag

return (

Boolean(type.prototype) &&

Boolean(type.prototype.isReactComponent)

);

}

// This function takes a React element (e.g. <App />)

// and returns a DOM or Native node representing the mounted tree.

function mount(element) {

var type = element.type;

var props = element.props;

// We will determine the rendered element

// by either running the type as function

// or creating an instance and calling render().

var renderedElement;

if (isClass(type)) {

// Component class

var publicInstance = new type(props);

// Set the props

publicInstance.props = props;

// Call the lifecycle if necessary

if (publicInstance.componentWillMount) {

publicInstance.componentWillMount();

}

// Get the rendered element by calling render()

renderedElement = publicInstance.render();

} else {

// Component function

renderedElement = type(props);

}

// This process is recursive because a component may

// return an element with a type of another component.

return mount(renderedElement);

// Note: this implementation is incomplete and recurses infinitely!

// It only handles elements like <App /> or <Button />.

// It doesn't handle elements like <div /> or <p /> yet.

}

var rootEl = document.getElementById('root');

var node = mount(<App />);

rootEl.appendChild(node);Note:

This really is a pseudo-code. It isn’t similar to the real implementation. It will also cause a stack overflow because we haven’t discussed when to stop the recursion.

Let’s recap a few key ideas in the example above:

- React elements are plain objects representing the component type (e.g.

App) and the props. - User-defined components (e.g.

App) can be classes or functions but they all “render to” elements. - “Mounting” is a recursive process that creates a DOM or Native tree given the top-level React element (e.g.

<App />).

Mounting Host Elements

This process would be useless if we didn’t render something to the screen as a result.

In addition to user-defined (“composite”) components, React elements may also represent platform-specific (“host”) components. For example, Button might return a <div /> from its render method.

If element’s type property is a string, we are dealing with a host element:

console.log(<div />);

// { type: 'div', props: {} }There is no user-defined code associated with host elements.

When the reconciler encounters a host element, it lets the renderer take care of mounting it. For example, React DOM would create a DOM node.

If the host element has children, the reconciler recursively mounts them following the same algorithm as above. It doesn’t matter whether children are host (like <div><hr /></div>), composite (like <div><Button /></div>), or both.

The DOM nodes produced by the child components will be appended to the parent DOM node, and recursively, the complete DOM structure will be assembled.

Note:

The reconciler itself is not tied to the DOM. The exact result of mounting (sometimes called “mount image” in the source code) depends on the renderer, and can be a DOM node (React DOM), a string (React DOM Server), or a number representing a native view (React Native).

If we were to extend the code to handle host elements, it would look like this:

function isClass(type) {

// React.Component subclasses have this flag

return (

Boolean(type.prototype) &&

Boolean(type.prototype.isReactComponent)

);

}

// This function only handles elements with a composite type.

// For example, it handles <App /> and <Button />, but not a <div />.

function mountComposite(element) {

var type = element.type;

var props = element.props;

var renderedElement;

if (isClass(type)) {

// Component class

var publicInstance = new type(props);

// Set the props

publicInstance.props = props;

// Call the lifecycle if necessary

if (publicInstance.componentWillMount) {

publicInstance.componentWillMount();

}

renderedElement = publicInstance.render();

} else if (typeof type === 'function') {

// Component function

renderedElement = type(props);

}

// This is recursive but we'll eventually reach the bottom of recursion when

// the element is host (e.g. <div />) rather than composite (e.g. <App />):

return mount(renderedElement);

}

// This function only handles elements with a host type.

// For example, it handles <div /> and <p /> but not an <App />.

function mountHost(element) {

var type = element.type;

var props = element.props;

var children = props.children || [];

if (!Array.isArray(children)) {

children = [children];

}

children = children.filter(Boolean);

// This block of code shouldn't be in the reconciler.

// Different renderers might initialize nodes differently.

// For example, React Native would create iOS or Android views.

var node = document.createElement(type);

Object.keys(props).forEach(propName => {

if (propName !== 'children') {

node.setAttribute(propName, props[propName]);

}

});

// Mount the children

children.forEach(childElement => {

// Children may be host (e.g. <div />) or composite (e.g. <Button />).

// We will also mount them recursively:

var childNode = mount(childElement);

// This line of code is also renderer-specific.

// It would be different depending on the renderer:

node.appendChild(childNode);

});

// Return the DOM node as mount result.

// This is where the recursion ends.

return node;

}

function mount(element) {

var type = element.type;

if (typeof type === 'function') {

// User-defined components

return mountComposite(element);

} else if (typeof type === 'string') {

// Platform-specific components

return mountHost(element);

}

}

var rootEl = document.getElementById('root');

var node = mount(<App />);

rootEl.appendChild(node);This is working but still far from how the reconciler is really implemented. The key missing ingredient is support for updates.

Introducing Internal Instances

The key feature of React is that you can re-render everything, and it won’t recreate the DOM or reset the state:

root.render(<App />);

// Should reuse the existing DOM:

root.render(<App />);However, our implementation above only knows how to mount the initial tree. It can’t perform updates on it because it doesn’t store all the necessary information, such as all the publicInstances, or which DOM nodes correspond to which components.

The stack reconciler codebase solves this by making the mount() function a method and putting it on a class. There are drawbacks to this approach, and we are going in the opposite direction in the ongoing rewrite of the reconciler. Nevertheless this is how it works now.

Instead of separate mountHost and mountComposite functions, we will create two classes: DOMComponent and CompositeComponent.

Both classes have a constructor accepting the element, as well as a mount() method returning the mounted node. We will replace a top-level mount() function with a factory that instantiates the correct class:

function instantiateComponent(element) {

var type = element.type;

if (typeof type === 'function') {

// User-defined components

return new CompositeComponent(element);

} else if (typeof type === 'string') {

// Platform-specific components

return new DOMComponent(element);

}

}First, let’s consider the implementation of CompositeComponent:

class CompositeComponent {

constructor(element) {

this.currentElement = element;

this.renderedComponent = null;

this.publicInstance = null;

}

getPublicInstance() {

// For composite components, expose the class instance.

return this.publicInstance;

}

mount() {

var element = this.currentElement;

var type = element.type;

var props = element.props;

var publicInstance;

var renderedElement;

if (isClass(type)) {

// Component class

publicInstance = new type(props);

// Set the props

publicInstance.props = props;

// Call the lifecycle if necessary

if (publicInstance.componentWillMount) {

publicInstance.componentWillMount();

}

renderedElement = publicInstance.render();

} else if (typeof type === 'function') {

// Component function

publicInstance = null;

renderedElement = type(props);

}

// Save the public instance

this.publicInstance = publicInstance;

// Instantiate the child internal instance according to the element.

// It would be a DOMComponent for <div /> or <p />,

// and a CompositeComponent for <App /> or <Button />:

var renderedComponent = instantiateComponent(renderedElement);

this.renderedComponent = renderedComponent;

// Mount the rendered output

return renderedComponent.mount();

}

}This is not much different from our previous mountComposite() implementation, but now we can save some information, such as this.currentElement, this.renderedComponent, and this.publicInstance, for use during updates.

Note that an instance of CompositeComponent is not the same thing as an instance of the user-supplied element.type. CompositeComponent is an implementation detail of our reconciler, and is never exposed to the user. The user-defined class is the one we read from element.type, and CompositeComponent creates an instance of it.

To avoid the confusion, we will call instances of CompositeComponent and DOMComponent “internal instances”. They exist so we can associate some long-lived data with them. Only the renderer and the reconciler are aware that they exist.

In contrast, we call an instance of the user-defined class a “public instance”. The public instance is what you see as this in the render() and other methods of your custom components.

The mountHost() function, refactored to be a mount() method on DOMComponent class, also looks familiar:

class DOMComponent {

constructor(element) {

this.currentElement = element;

this.renderedChildren = [];

this.node = null;

}

getPublicInstance() {

// For DOM components, only expose the DOM node.

return this.node;

}

mount() {

var element = this.currentElement;

var type = element.type;

var props = element.props;

var children = props.children || [];

if (!Array.isArray(children)) {

children = [children];

}

// Create and save the node

var node = document.createElement(type);

this.node = node;

// Set the attributes

Object.keys(props).forEach(propName => {

if (propName !== 'children') {

node.setAttribute(propName, props[propName]);

}

});

// Create and save the contained children.

// Each of them can be a DOMComponent or a CompositeComponent,

// depending on whether the element type is a string or a function.

var renderedChildren = children.map(instantiateComponent);

this.renderedChildren = renderedChildren;

// Collect DOM nodes they return on mount

var childNodes = renderedChildren.map(child => child.mount());

childNodes.forEach(childNode => node.appendChild(childNode));

// Return the DOM node as mount result

return node;

}

}The main difference after refactoring from mountHost() is that we now keep this.node and this.renderedChildren associated with the internal DOM component instance. We will also use them for applying non-destructive updates in the future.

As a result, each internal instance, composite or host, now points to its child internal instances. To help visualize this, if a function <App> component renders a <Button> class component, and Button class renders a <div>, the internal instance tree would look like this:

[object CompositeComponent] {

currentElement: <App />,

publicInstance: null,

renderedComponent: [object CompositeComponent] {

currentElement: <Button />,

publicInstance: [object Button],

renderedComponent: [object DOMComponent] {

currentElement: <div />,

node: [object HTMLDivElement],

renderedChildren: []

}

}

}In the DOM you would only see the <div>. However the internal instance tree contains both composite and host internal instances.

The composite internal instances need to store:

- The current element.

- The public instance if element type is a class.

- The single rendered internal instance. It can be either a

DOMComponentor aCompositeComponent.

The host internal instances need to store:

- The current element.

- The DOM node.

- All the child internal instances. Each of them can be either a

DOMComponentor aCompositeComponent.

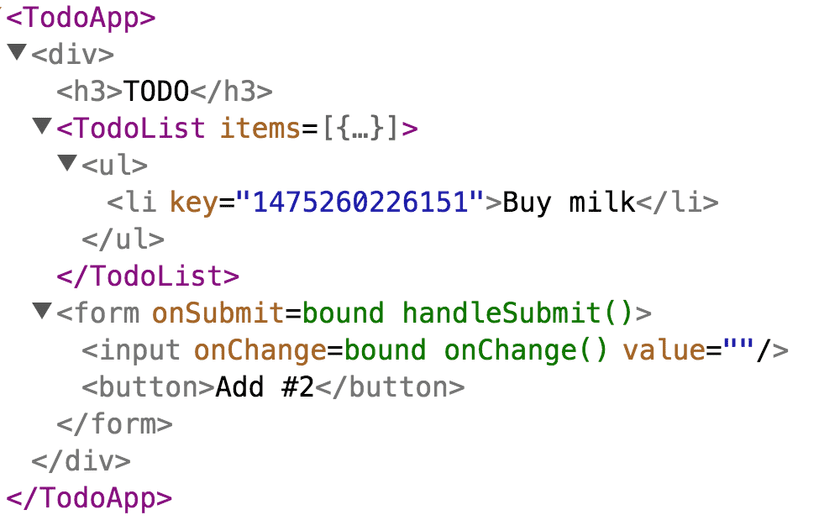

If you’re struggling to imagine how an internal instance tree is structured in more complex applications, React DevTools can give you a close approximation, as it highlights host instances with grey, and composite instances with purple:

To complete this refactoring, we will introduce a function that mounts a complete tree into a container node and a public instance:

function mountTree(element, containerNode) {

// Create the top-level internal instance

var rootComponent = instantiateComponent(element);

// Mount the top-level component into the container

var node = rootComponent.mount();

containerNode.appendChild(node);

// Return the public instance it provides

var publicInstance = rootComponent.getPublicInstance();

return publicInstance;

}

var rootEl = document.getElementById('root');

mountTree(<App />, rootEl);Unmounting

Now that we have internal instances that hold onto their children and the DOM nodes, we can implement unmounting. For a composite component, unmounting calls a lifecycle method and recurses.

class CompositeComponent {

// ...

unmount() {

// Call the lifecycle method if necessary

var publicInstance = this.publicInstance;

if (publicInstance) {

if (publicInstance.componentWillUnmount) {

publicInstance.componentWillUnmount();

}

}

// Unmount the single rendered component

var renderedComponent = this.renderedComponent;

renderedComponent.unmount();

}

}For DOMComponent, unmounting tells each child to unmount:

class DOMComponent {

// ...

unmount() {

// Unmount all the children

var renderedChildren = this.renderedChildren;

renderedChildren.forEach(child => child.unmount());

}

}In practice, unmounting DOM components also removes the event listeners and clears some caches, but we will skip those details.

We can now add a new top-level function called unmountTree(containerNode) that is similar to ReactDOM.unmountComponentAtNode():

function unmountTree(containerNode) {

// Read the internal instance from a DOM node:

// (This doesn't work yet, we will need to change mountTree() to store it.)

var node = containerNode.firstChild;

var rootComponent = node._internalInstance;

// Unmount the tree and clear the container

rootComponent.unmount();

containerNode.innerHTML = '';

}In order for this to work, we need to read an internal root instance from a DOM node. We will modify mountTree() to add the _internalInstance property to the root DOM node. We will also teach mountTree() to destroy any existing tree so it can be called multiple times:

function mountTree(element, containerNode) {

// Destroy any existing tree

if (containerNode.firstChild) {

unmountTree(containerNode);

}

// Create the top-level internal instance

var rootComponent = instantiateComponent(element);

// Mount the top-level component into the container

var node = rootComponent.mount();

containerNode.appendChild(node);

// Save a reference to the internal instance

node._internalInstance = rootComponent;

// Return the public instance it provides

var publicInstance = rootComponent.getPublicInstance();

return publicInstance;

}Now, running unmountTree(), or running mountTree() repeatedly, removes the old tree and runs the componentWillUnmount() lifecycle method on components.

Updating

In the previous section, we implemented unmounting. However React wouldn’t be very useful if each prop change unmounted and mounted the whole tree. The goal of the reconciler is to reuse existing instances where possible to preserve the DOM and the state:

var rootEl = document.getElementById('root');

mountTree(<App />, rootEl);

// Should reuse the existing DOM:

mountTree(<App />, rootEl);We will extend our internal instance contract with one more method. In addition to mount() and unmount(), both DOMComponent and CompositeComponent will implement a new method called receive(nextElement):

class CompositeComponent {

// ...

receive(nextElement) {

// ...

}

}

class DOMComponent {

// ...

receive(nextElement) {

// ...

}

}Its job is to do whatever is necessary to bring the component (and any of its children) up to date with the description provided by the nextElement.

This is the part that is often described as “virtual DOM diffing” although what really happens is that we walk the internal tree recursively and let each internal instance receive an update.

Updating Composite Components

When a composite component receives a new element, we run the componentWillUpdate() lifecycle method.

Then we re-render the component with the new props, and get the next rendered element:

class CompositeComponent {

// ...

receive(nextElement) {

var prevProps = this.currentElement.props;

var publicInstance = this.publicInstance;

var prevRenderedComponent = this.renderedComponent;

var prevRenderedElement = prevRenderedComponent.currentElement;

// Update *own* element

this.currentElement = nextElement;

var type = nextElement.type;

var nextProps = nextElement.props;

// Figure out what the next render() output is

var nextRenderedElement;

if (isClass(type)) {

// Component class

// Call the lifecycle if necessary

if (publicInstance.componentWillUpdate) {

publicInstance.componentWillUpdate(nextProps);

}

// Update the props

publicInstance.props = nextProps;

// Re-render

nextRenderedElement = publicInstance.render();

} else if (typeof type === 'function') {

// Component function

nextRenderedElement = type(nextProps);

}

// ...Next, we can look at the rendered element’s type. If the type has not changed since the last render, the component below can also be updated in place.

For example, if it returned <Button color="red" /> the first time, and <Button color="blue" /> the second time, we can just tell the corresponding internal instance to receive() the next element:

// ...

// If the rendered element type has not changed,

// reuse the existing component instance and exit.

if (prevRenderedElement.type === nextRenderedElement.type) {

prevRenderedComponent.receive(nextRenderedElement);

return;

}

// ...However, if the next rendered element has a different type than the previously rendered element, we can’t update the internal instance. A <button> can’t “become” an <input>.

Instead, we have to unmount the existing internal instance and mount the new one corresponding to the rendered element type. For example, this is what happens when a component that previously rendered a <button /> renders an <input />:

// ...

// If we reached this point, we need to unmount the previously

// mounted component, mount the new one, and swap their nodes.

// Find the old node because it will need to be replaced

var prevNode = prevRenderedComponent.getHostNode();

// Unmount the old child and mount a new child

prevRenderedComponent.unmount();

var nextRenderedComponent = instantiateComponent(nextRenderedElement);

var nextNode = nextRenderedComponent.mount();

// Replace the reference to the child

this.renderedComponent = nextRenderedComponent;

// Replace the old node with the new one

// Note: this is renderer-specific code and

// ideally should live outside of CompositeComponent:

prevNode.parentNode.replaceChild(nextNode, prevNode);

}

}To sum this up, when a composite component receives a new element, it may either delegate the update to its rendered internal instance, or unmount it and mount a new one in its place.

There is another condition under which a component will re-mount rather than receive an element, and that is when the element’s key has changed. We don’t discuss key handling in this document because it adds more complexity to an already complex tutorial.

Note that we needed to add a method called getHostNode() to the internal instance contract so that it’s possible to locate the platform-specific node and replace it during the update. Its implementation is straightforward for both classes:

class CompositeComponent {

// ...

getHostNode() {

// Ask the rendered component to provide it.

// This will recursively drill down any composites.

return this.renderedComponent.getHostNode();

}

}

class DOMComponent {

// ...

getHostNode() {

return this.node;

}

}Updating Host Components

Host component implementations, such as DOMComponent, update differently. When they receive an element, they need to update the underlying platform-specific view. In case of React DOM, this means updating the DOM attributes:

class DOMComponent {

// ...

receive(nextElement) {

var node = this.node;

var prevElement = this.currentElement;

var prevProps = prevElement.props;

var nextProps = nextElement.props;

this.currentElement = nextElement;

// Remove old attributes.

Object.keys(prevProps).forEach(propName => {

if (propName !== 'children' && !nextProps.hasOwnProperty(propName)) {

node.removeAttribute(propName);

}

});

// Set next attributes.

Object.keys(nextProps).forEach(propName => {

if (propName !== 'children') {

node.setAttribute(propName, nextProps[propName]);

}

});

// ...Then, host components need to update their children. Unlike composite components, they might contain more than a single child.

In this simplified example, we use an array of internal instances and iterate over it, either updating or replacing the internal instances depending on whether the received type matches their previous type. The real reconciler also takes element’s key in the account and track moves in addition to insertions and deletions, but we will omit this logic.

We collect DOM operations on children in a list so we can execute them in batch:

// ...

// These are arrays of React elements:

var prevChildren = prevProps.children || [];

if (!Array.isArray(prevChildren)) {

prevChildren = [prevChildren];

}

var nextChildren = nextProps.children || [];

if (!Array.isArray(nextChildren)) {

nextChildren = [nextChildren];

}

// These are arrays of internal instances:

var prevRenderedChildren = this.renderedChildren;

var nextRenderedChildren = [];

// As we iterate over children, we will add operations to the array.

var operationQueue = [];

// Note: the section below is extremely simplified!

// It doesn't handle reorders, children with holes, or keys.

// It only exists to illustrate the overall flow, not the specifics.

for (var i = 0; i < nextChildren.length; i++) {

// Try to get an existing internal instance for this child

var prevChild = prevRenderedChildren[i];

// If there is no internal instance under this index,

// a child has been appended to the end. Create a new

// internal instance, mount it, and use its node.

if (!prevChild) {

var nextChild = instantiateComponent(nextChildren[i]);

var node = nextChild.mount();

// Record that we need to append a node

operationQueue.push({type: 'ADD', node});

nextRenderedChildren.push(nextChild);

continue;

}

// We can only update the instance if its element's type matches.

// For example, <Button size="small" /> can be updated to

// <Button size="large" /> but not to an <App />.

var canUpdate = prevChildren[i].type === nextChildren[i].type;

// If we can't update an existing instance, we have to unmount it

// and mount a new one instead of it.

if (!canUpdate) {

var prevNode = prevChild.getHostNode();

prevChild.unmount();

var nextChild = instantiateComponent(nextChildren[i]);

var nextNode = nextChild.mount();

// Record that we need to swap the nodes

operationQueue.push({type: 'REPLACE', prevNode, nextNode});

nextRenderedChildren.push(nextChild);

continue;

}

// If we can update an existing internal instance,

// just let it receive the next element and handle its own update.

prevChild.receive(nextChildren[i]);

nextRenderedChildren.push(prevChild);

}

// Finally, unmount any children that don't exist:

for (var j = nextChildren.length; j < prevChildren.length; j++) {

var prevChild = prevRenderedChildren[j];

var node = prevChild.getHostNode();

prevChild.unmount();

// Record that we need to remove the node

operationQueue.push({type: 'REMOVE', node});

}

// Point the list of rendered children to the updated version.

this.renderedChildren = nextRenderedChildren;

// ...As the last step, we execute the DOM operations. Again, the real reconciler code is more complex because it also handles moves:

// ...

// Process the operation queue.

while (operationQueue.length > 0) {

var operation = operationQueue.shift();

switch (operation.type) {

case 'ADD':

this.node.appendChild(operation.node);

break;

case 'REPLACE':

this.node.replaceChild(operation.nextNode, operation.prevNode);

break;

case 'REMOVE':

this.node.removeChild(operation.node);

break;

}

}

}

}And that is it for updating host components.

Top-Level Updates

Now that both CompositeComponent and DOMComponent implement the receive(nextElement) method, we can change the top-level mountTree() function to use it when the element type is the same as it was the last time:

function mountTree(element, containerNode) {

// Check for an existing tree

if (containerNode.firstChild) {

var prevNode = containerNode.firstChild;

var prevRootComponent = prevNode._internalInstance;

var prevElement = prevRootComponent.currentElement;

// If we can, reuse the existing root component

if (prevElement.type === element.type) {

prevRootComponent.receive(element);

return;

}

// Otherwise, unmount the existing tree

unmountTree(containerNode);

}

// ...

}Now calling mountTree() two times with the same type isn’t destructive:

var rootEl = document.getElementById('root');

mountTree(<App />, rootEl);

// Reuses the existing DOM:

mountTree(<App />, rootEl);These are the basics of how React works internally.

What We Left Out

This document is simplified compared to the real codebase. There are a few important aspects we didn’t address:

- Components can render

null, and the reconciler can handle “empty slots” in arrays and rendered output. - The reconciler also reads

keyfrom the elements, and uses it to establish which internal instance corresponds to which element in an array. A bulk of complexity in the actual React implementation is related to that. - In addition to composite and host internal instance classes, there are also classes for “text” and “empty” components. They represent text nodes and the “empty slots” you get by rendering

null. - Renderers use injection to pass the host internal class to the reconciler. For example, React DOM tells the reconciler to use

ReactDOMComponentas the host internal instance implementation. - The logic for updating the list of children is extracted into a mixin called

ReactMultiChildwhich is used by the host internal instance class implementations both in React DOM and React Native. - The reconciler also implements support for

setState()in composite components. Multiple updates inside event handlers get batched into a single update. - The reconciler also takes care of attaching and detaching refs to composite components and host nodes.

- Lifecycle methods that are called after the DOM is ready, such as

componentDidMount()andcomponentDidUpdate(), get collected into “callback queues” and are executed in a single batch. - React puts information about the current update into an internal object called “transaction”. Transactions are useful for keeping track of the queue of pending lifecycle methods, the current DOM nesting for the warnings, and anything else that is “global” to a specific update. Transactions also ensure React “cleans everything up” after updates. For example, the transaction class provided by React DOM restores the input selection after any update.

Jumping into the Code

ReactMountis where the code likemountTree()andunmountTree()from this tutorial lives. It takes care of mounting and unmounting top-level components.ReactNativeMountis its React Native analog.ReactDOMComponentis the equivalent ofDOMComponentin this tutorial. It implements the host component class for React DOM renderer.ReactNativeBaseComponentis its React Native analog.ReactCompositeComponentis the equivalent ofCompositeComponentin this tutorial. It handles calling user-defined components and maintaining their state.instantiateReactComponentcontains the switch that picks the right internal instance class to construct for an element. It is equivalent toinstantiateComponent()in this tutorial.ReactReconcileris a wrapper withmountComponent(),receiveComponent(), andunmountComponent()methods. It calls the underlying implementations on the internal instances, but also includes some code around them that is shared by all internal instance implementations.ReactChildReconcilerimplements the logic for mounting, updating, and unmounting children according to thekeyof their elements.ReactMultiChildimplements processing the operation queue for child insertions, deletions, and moves independently of the renderer.mount(),receive(), andunmount()are really calledmountComponent(),receiveComponent(), andunmountComponent()in React codebase for legacy reasons, but they receive elements.- Properties on the internal instances start with an underscore, e.g.

_currentElement. They are considered to be read-only public fields throughout the codebase.

Future Directions

Stack reconciler has inherent limitations such as being synchronous and unable to interrupt the work or split it in chunks. There is a work in progress on the new Fiber reconciler with a completely different architecture. In the future, we intend to replace stack reconciler with it, but at the moment it is far from feature parity.

Next Steps

Read the next section to learn about the guiding principles we use for React development.